Earle Olsen

artist

My current project is a family history of art and life called Daddy-O. In it, I delve into my father’s career as a painter in 1950s New York City and my grandfather’s career as a commercial designer in early 20th-century Chicago. You’ll find more about Earle’s work on this website. You can find more of my writing about his work in the archive of my Substack, From Life. Or subscribe here.

Nature Calls (Mitchell-Monet)

I had never been to the Bois de Boulogne and arrived early on the opening day of the “Monet Mitchell” exhibit to look around.

Journey to River’s Edge

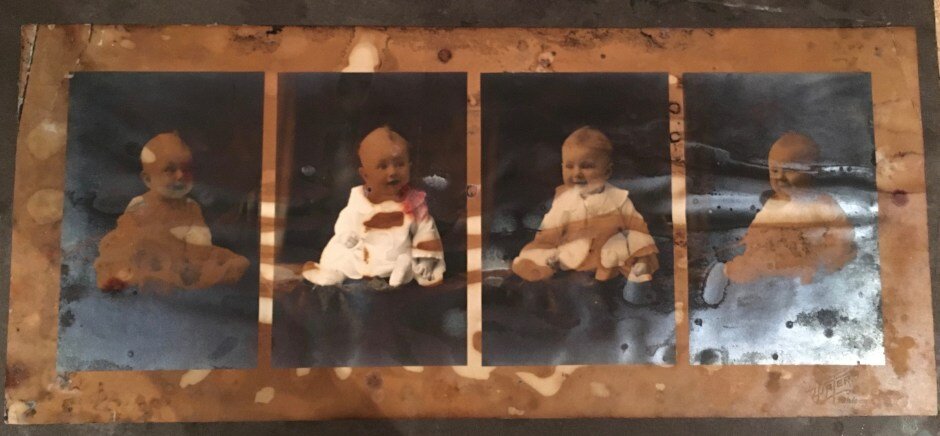

My artist father had a wonderful eye—great taste and an effortless sense of color and composition. Was it learned or instinctive, from his experiences or his body? I don’t know. But he had a literal eye, too. Two of them, bluish-gray. That’s what I miss since he died ten years ago: his eyes and his face. In other words, his presence.

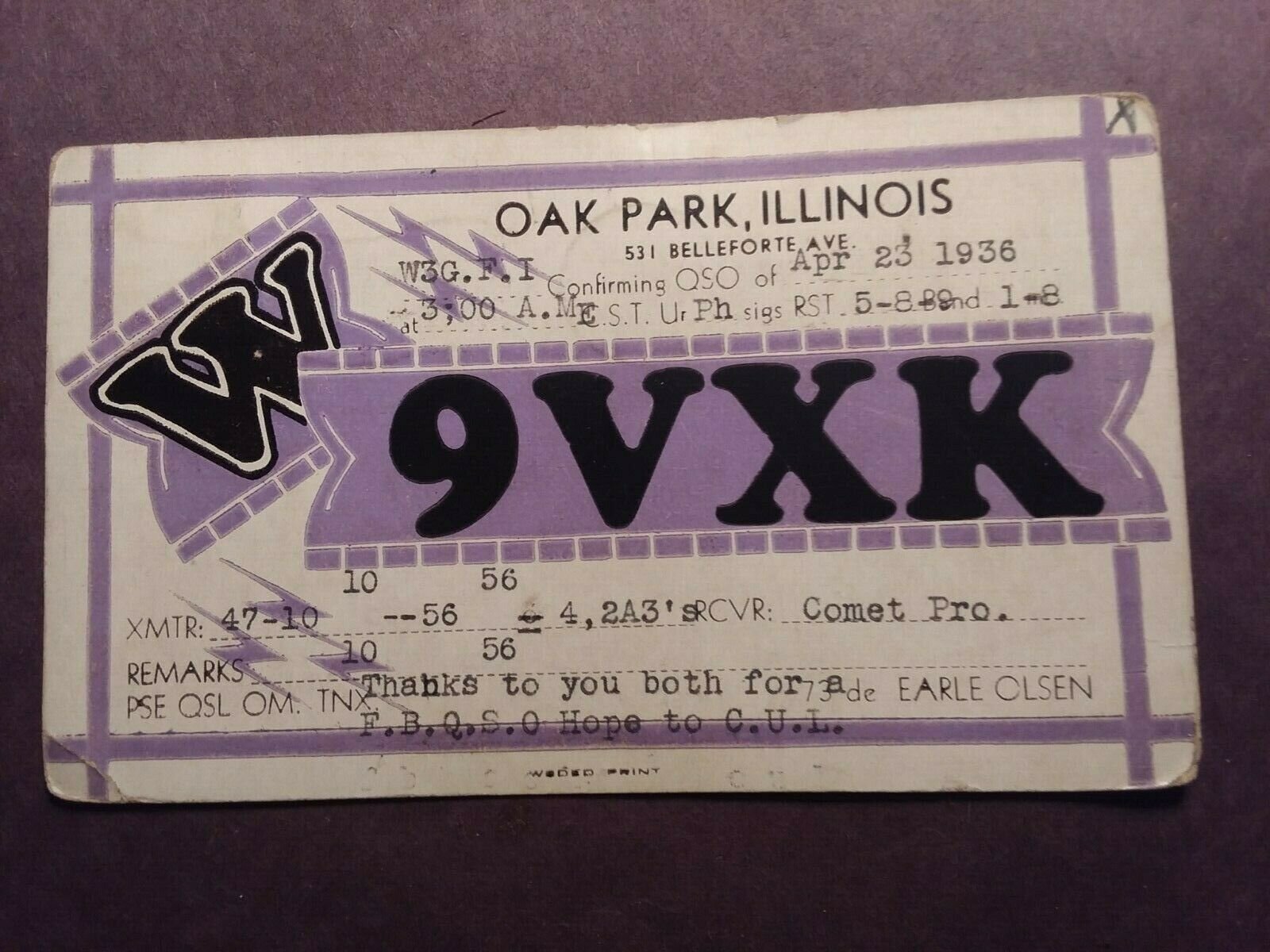

Mixed Signals

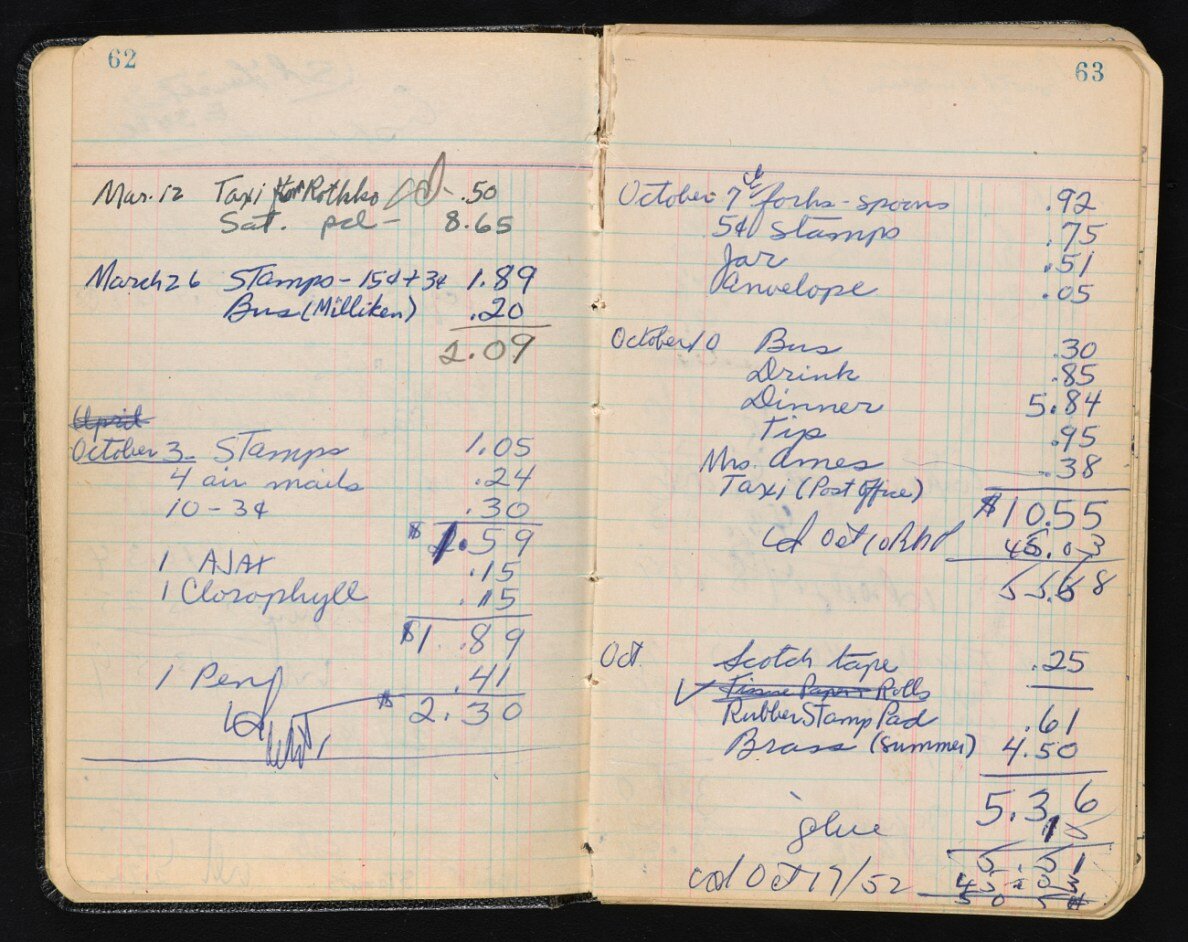

It’s been about a year since I last updated my blog. What a year, huh? I finished drafting the family memoir detailed on these pages, wrote case studies for tech companies, trained and coached product managers, and sheltered in place. No more research trips! But there is still much to find—or stumble upon—online.

Rabbit Hole #1

When I’m not sure what I’m doing with my family history project I can always do more research. Mostly that means chasing down names in the endless stream of associations that veer further and further from my father. One person (from his school, from his gallery, from an exhibit he was in) knows another person who knew another person. It’s a rabbit hole, yes, and more fun than productive, usually. Except that it can circle back or show patterns. You never know. Here’s one example from the last few days.

In the Archives

On the way home from Washington, D.C. it’s hard to type on the swaying train, with a laptop on my lap. I’ve spent two days at the Smithsonian Museum’s Archives of American Art, where I had a great time but found little of value among the saved records of my father’s friends and associates in the New York City art world of the 1950s and 1960s. I searched five boxes of records from Grace Borgenicht’s gallery for references to my father, who showed there in 1958. I found exactly one line item: the sale of his drawing “Orange Flowers” to the Whitney in 1956 for $100. Listed on a ledger page of sales to the Whitney from 1953-68, it was the lowest price of any of them. His friend Randall Morgan sold two works to the Whitney for $247.50 and $427.50. The highest price on that page was for a Leonard Baskin at $9,000.

Vital Records

Life stories depend on birth and deaths; they frame the narrative, so to speak, with a start and endpoint. But for genealogists and family historians, they are trickier than you’d think, even in the modern era (in the administrative sense of modern: ie. after governments starting keeping civil records, usually in the nineteenth century).

Pre-Story

The making of meaning starts with evidence, the data points that stretch like beads along a thread of thinking. In this metaphor pieces of evidence are like shells on the beach: three-dimensional objects of various shapes and sizes and origins that one might look for actively or come across by accident. But evidence can also be abstract, like a memory or a sensation, an experience that becomes a poem for an artist or an insight for a psychologist, a bodily symptom that leads to a medical diagnosis. It can be a story, a song, a smell, or a taste, like Proust’s madeleine.